Katuosoite

FI-00410 Helsinki 41

FINLAND

Prof. Dr. Douglas J. Robinson,

Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen,

2001 Longxiang Boulevard, Longgang District,

Shenzhen 518172,

CHINA

September 15, 2022

Dear Dr. Robinson:

It is with astute interest and wonder that I have been reading your 2016 book Semiotranslating Peirce in which you allegedly use my Finnish anthology of writings by Charles S. Peirce, Johdatus tieteen logiikkaan ja muita kirjoituksia, from 2001 as an item for a case study, and I have a few words to say about your monograph. I’ll explain later why I’m writing precisely now, six years post festum, so to speak.

1. I begin with mentioning that there are some good ideas in your book; certain sections, however, reveal unscholarly and partial attitude and slipshod reasoning. There are both minor and major issues, and I’ll discuss them in a loose consecutive order.

2. The first sign of alarm is encountered on page 7 where you assign the abbreviation JTL to my anthology. You explain that the English-language title of this book would be “Introduction to the Logic of Science and Other Writings.” Unfortunately this is wrong. As you surely know, Peirce labelled his six-part article series from 1877–78 as “Illustrations of the Logic of Science,” and this heading should be used when rendering the title of my anthology into English: “Illustrations of the Logic of Science and Other Writings.” This will make it immediately clear to all readers of Peirce what the anthology is about.

3. Your criticism of the word laatumerkki as a semiotic term (qualisign) seems artificial (pp. 37–38, 42, 53). There are many words that mean different things in different branches of life. For instance, both economists and psychologists can use the Finnish verb sijoittaa and the former mean ‘to invest’ with it and the latter ‘to project.’ To a lawyer, pesä means a different thing than to an ornithologist. In English, sublimation means one thing to a physicist and another to a psychologist. Do you really mean that one usage should push the other away? Are the communities of psychologists or physicists wrong? Is this a zero-sum game?

Your Google argument, on the other hand, is badly flawed and your numbers are misguided. Now you are not a computer scientist, and clearly you don’t understand how Google presents and modifies its search results. I can see that you have two false assumptions.

For the first, you do not realize that Google adapts the search results individually for every user, based upon his or her previous search history, user language, location, and possible search settings. A user may or may not have an account at Google, but his or her search history and other habits are tracked with software items called “cookies.” Even if you think that everybody gets exactly the same results when they type the word laatumerkki in the Google search bar, that is not true.

Didn’t you notice anything strange in the fact that Google.com gave you 11,000 hits and Google.fi 54,000 hits? Both engines draw from exactly the same base, namely the Internet. Why such a substantial difference?

Thus we come to your second false assumption. The amounts that Google gives you on the first page of the search results are fictitious – they are bluff. You didn’t go specifically to the 11,000th or to the 54,000th result and see what it happened to be, did you? No, you believed the number that was shown on the first page. Actually you have to go to the last page of results to see the true number of occurrences. I did that for the nominative case of laatumerkki on Google.com and got the following results: first page, “About 127 000 results,” (nice!!) but when I got to the last page available – “Page 15 of about 141 results.” So, the promised 127,000 results melted down to 141 actual hits! As this is quite fun, here you have the preliminary and final results for genitive and partitive cases:

laatumerkin 20,600 → 121

laatumerkkiä 5,200 → 150.

(One has to use quotation marks for exact searches.) Your 54,000 hits appear to have gone, clean vanished away like the beautiful Melusina of the fable.

There is also a third flaw in your reasoning: you didn’t investigate whether in any of those hits the word laatumerkki might actually be used in a semiotic sense. That would have been easy: search for pages which have both of the words laatumerkki and Peirce or laatumerkki and semiotiikka. I did that – results: 81 → 26 and 418 → 55, respectively. Few of those hits actually come from serious sites, but the word seems to have some minor acceptance at least, although it’s not “widespread.” Who needs to boast with tens of thousands of Web hits anyway? Many printed texts are not available on-line.

4. Next (starting on page 38) you attack the Finnish word tulkinnos, used for interpretant. You keep calling it my invention, but it is not. If you care to look in Professor Eero Tarasti’s book Johdatusta semiotiikkaan from 1990, it mentions “tulkitsin” as a Finnish translation for Peirce’s term and Aatos Ojala as the inventor. A bit later, however, Tarasti told in his lecture that someone had preferred the word tulkinnos and since then I have used it. That was early 1990s and I don’t remember anymore whom Tarasti referred to. If you think this is important, you can ask him directly. — On the same page, 38, you write kvaali but “kvalimerkki.” The latter is incorrect.

On pages 42–43 you keep claiming that interpretantti and tulkinnos would sound equally foreign to a Finnish-speaking layman. That is not true. Interpretantti definitely appears a foreign loan word and tulkinnos sounds something indigenous to a native speaker of Finnish, a product of interpreting (cf. yskiä > yskös, painaa > painos, väärentää > väärennös). Some recent writers use the form tulkinne, perhaps just to differentiate themselves from me.

5. It is problematic to apply conceptions from the U.S. publishing industry to that of Finland. This country is poor and we only have “state universities,” accessible to all, no term fees. There are no wealthy University Presses here who would have unlimited resources to publish the classics in posh editions. I guess the following description on p. 41 is formulated to make the publishing history of Johdatus to look a bit suspect, or fishy, from an American point of view:

“Lång, who (1) published his translation with an independent trade press and (2) is a freelance translator who doesn’t need to worry about academic hiring and promotion [...].”

My publisher Osuuskunta Vastapaino is among the best scholarly publishers there are in Finland. I don’t know who would have been more appropriate. As the verso of the title page states, we received grants from three organizations and these were imperative prerequisites for the project. It was the best this country could afford in a case like this. But I could have used an additional month or two to work on the anthology.

Most translators in Finland are freelancers, and they really have to worry about further hiring and reputation, even academic. After all, I never received a scholarship for post-doctoral research, but I don’t know how much the calamity with Johdatus actually contributed to that.

Still, your approach is typically American: one’s academic position is of paramount importance and all outsiders are suspicious. How come they chose to fail, to be ostracized?

6. We seem to have a different notion about authority as well. Probably Mats Bergman and Sami Paavola and the other critics you cite are indeed notable experts in Peirce studies, but they have no authority or competence in Fennistics, that is, in the study of the Finnish language. (Finnish language was my secondary subject at the university.) They cannot even be called amateurs, as an amateur is someone who loves (amare) his or her subject. Jag vet inte om Mats Bergman ens talar finska som modersmål. It appears to me that Sami Paavola simply cannot write a single clause in grammatically correct Finnish. He breaks the punctuation rules so obstinately that it smacks of pubescent defiance, and it’s tiresome to read him in his alleged mother tongue. Him we can usually only commiserate, as a person with a congenital defect. Few people can take this posse seriously when they proclaim their opinions of and regulations for the Finnish language.

For instance, Bergman & Paavola keep mocking the word kotoperäinen. They seem never to have realized that it is a neutral and common term in Fennistics, not humorous, not colloquial. This is evident to anyone who has read or contributed to Virittäjä.

7. In my doctoral thesis I discussed the scientific status of psychoanalysis in the light of knowledge theory and modern virtue epistemology, and its use within musicology. It took me seven years to write the thesis, almost four years of them full-time. Four organizations presented me with stipends for research. I have also written peer-reviewed articles on these subjects, acted as a peer-reviewer for musicological and psychoanalytical journals myself, and translated and edited ten books by Sigmund Freud into Finnish.

Now in this country a doctor is automatically considered an expert and a professional in his or her field of study. Despite that you characterize me on page 42 as following:

“Lång is neither quite an in-grouper in academia nor quite an out-grouper. He has a PhD in musicology and an amateur interest in philosophy and psychoanalysis [...].”

Obviously your characterization is meant to insult and to disparage me in the eyes of the scholarly community, and it may constitute a libel (or rather an attempted libel). There are, fortunately, several reasons why your estimations mustn’t be taken seriously. First of all, you have not read my thesis or articles on those subjects, and therefore cannot judge whether they really are professional or amateurish quality. You aren’t an expert in philosophy or in psychoanalysis either, and you aren’t a part of Finland’s academia and don’t know for sure who’s in and who’s out, especially within musicology in this country. You are merely echoing the biased opinions (hearsay) of Bergman, Paavola, Pihlström and others, whose repugnance has clouded their judgement. (What ever happened to γνῶθι σεαυτόν?)

It seems to me that you have chosen your bedfellows poorly. The one-sided sentiments they have fed you with may not be so reliable after all. From your text I conclude that they have continued their derision, privately, well in the 2010s.

When you claim (or let it be claimed through you) that a Finnish doctor of philosophy is but an amateur in his field of expertise, you really need to establish the truth of such a proposition – the onus probandi is on you. So far you have not supplied any evidence, however, merely mud-throwing, and such isn’t proper academic courtesy. Has the University of Helsinki really passed an amateurish doctoral thesis? Have all my supervisors, examiners and editors and reviewers (including those at Niin & näin) been dupes? Is the University of Helsinki a mere diploma mill?

Let’s see if we could assassinate the character of one Charles Sanders Peirce in your manner:

“Mr. Peirce has no academic position. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in chemistry, and has an amateur interest in metaphysics and French language. A failing out-grouper, he has been unemployed since 1884, known to default his financial debts. He is divorced, and quickly re-married to an un-American woman of dubious extraction.”

Your description is not fully useless, though. When someone begs a piece of writing or an interview from me and I don’t have time for it, I simply refer them to your book.

Incidentally, you are not the only one who wished to debunk my doctoral thesis as amateurish. Professor Jeja Pekka Roos and his minions read a few pages of the 320-page thesis, and because of my criticism of sociobiology they claimed that the whole work is rubbish. At the disputation, however, they did not speak up when I asked anyone to do so.

8. Have you ever heard of the Latin phrase audiatur et altera pars? On pages 19–20 and 54 you mention that you let Sami Paavola and Tommi Uschanov, among others, read the manuscript of chapters. I was not allowed such privilege, although I could already then have pointed out your misconceptions and perhaps improved the book; I presume Heikki Nyman was similarly kept in the dark, although he could have provided helpful comments and suggested corrections of his own as well. But you had concocted a good story – why spoil it with facts?

9. When Johdatus was published in 2001, it received mixed reviews. Only Niin & näin was overtly hostile, others were more or less neutral and one was positive. It is one-sided of you to fix on the opponents and let yourself to be used as a tool for bashing the translator (still after fifteen years).

Also, you remain silent on the double role of Bergman & Paavola. As mentioned in my preface, they participated in the translation process, although they didn’t actually read anything but stressed instead that they were very busy; still I was able to consult them and received some helpful advice. When discussing selected essays, some other readers from the philosophical circles, however, provided not only useful comments but also suggestions that from the point of view of a professional translator and a Fennistic scholar seemed naïve, misguided and impractical. In my blunt way, I discussed these fallacies in the preface, without realizing that I might actually offend those mentioned at the end of it, including Bergman & Paavola – a vile reward for their pro bono efforts. Still, you should have contextualized this mutual criticism in your book, and shown that Bergman & Paavola, Vehkavaara and Pihlström aren’t merely some chance, objective outsiders but previous participants in the translation project as well.

However, I keep feeling that the criticism I expressed was justified, although gruff; the feedback that the manuscript of Johdatus received was not always apt, and I was anticipating that those opinions would reappear also in the book reviews.

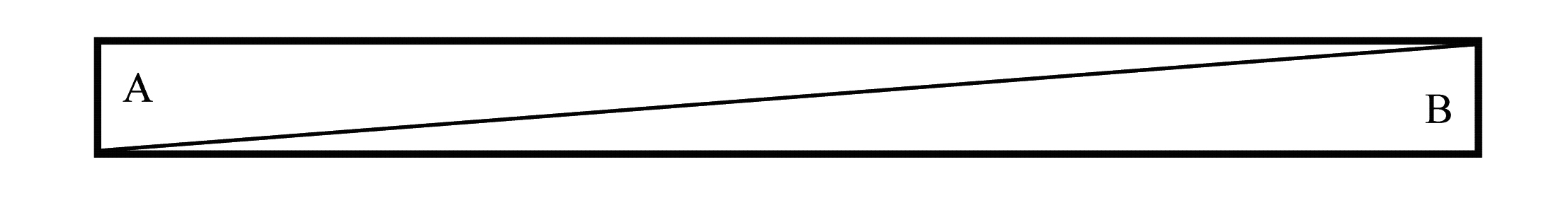

10. As for the wrangle between foreignization and domestication, let me illustrate my views with a simple pseudo-mathematical model. Imagine a continuum and two variables, A and B. At the left end of the continuum, the value of A is 100 % and that of B is 0 %. When you move from left to right, the value of A decreases continuously and the value of B similarly increases so that their combined value is always 100 %. In the middle, the value of both A and B is 50 %, and at the right end, the value of A is 0 % and that of B is 100 %. It might look something like this:

Now let’s call A “Græco-Roman” and B “Finnlandisierung” and illustrate the guiding principle of a Finnish translator with them. At the left extremity, a translator would only use Greek- and Latin-based words (like interpretantti) in his or her Finnish translation. In practice, such a rendering would be unreadable because foreign words would be used excessively, for the mere sake of using them. Then, at the right extremity, the translator would always choose indigenous words and neologisms created from them (like tulkinnos). That translation, too, would make a very tedious reading, and no translator actually would proceed according to either extremity.

In real life, every translator instead takes some middle course, happy mean, between the extremities; an exact numerical value cannot be determined for this (only a fuzzy estimation), but in comparative cases you may note that one translator has been somewhat closer to the left extremity and another closer to the right one, stressing slightly either variable – but both of them still relatively close to the middle.

When translating Johdatus, I did go close to a right extremity, merely hoping that the general usage would then be nudged slightly from the Græco-Roman to the Finnlandisierung end, still, of course, remaining in the reasonable middle. (It’s like towing a truck with a rubber band.) From a contemporary point of view, that could be labelled as a hypothesis, and obviously not a very successful one.

Additionally, the example of the Estonian language both inspired and worried me as foreign loan words are rather popular there; on the other hand, Estonian also has a tradition of aweless neologisms, keeleuuendus, with Johannes Aavik and others creating new words for the young national language. — I also mentioned the influence of George Orwell (“Politics and the English Language”).

Bergman & Paavola, however, reproach me for not going all the way to the Finnlandisierung extremity; but no one in his or her right mind would go so far. To avoid an extremity is not an inconsistency but a compromise that everyone has to make in one form or another. It is a continuum, not an either/or dichotomy.

À propos, their attitude reminds me of the example “Mr. Müller is a Jew” in S. I. Hayakawa’s book Language in Thought and Action. The poor Israelite simply cannot do anything right, and I can identify myself with him.

Also you claim it inconsistent (on p. 36) of me to use the foreign word propensiteetti. The footnote on page 195/204 in Johdatus, however, presents “propensiteetti- eli taipuvaisuustulkinta”; subsequently, I would have used the word taipuvaisuustulkinta.

Contrary to what you appear to think, I never intended to change the actual parlance of philosophy as radically as Johdatus has (or rather my critics have) allured you to assume. For instance, if someone really started to use the triad kuva–osoitin–tunnus, I would be surprised and even a bit concerned. Thus, there is a hint of an artistic manifesto in the anthology, not only in the preface but also in the translations and rejoinders.

As it happened, I inadvertently caused an opposite reaction towards Græco-Roman because philosophers detested the anthology (and the belligerent translator) so deeply. That was the tragedy of the book and it taught me a lesson. Since then, my translations haven’t caused a scandal anymore; instead, I’ve served my readers to my best ability.

11. The dotted list on pages 46–47 seems to consist of hostile projections which tell more about the projecting person than the object of those projections (my views and intentions). It’s private ranting. I skip this section, and recommend others to do so as well.

12. You keep attributing the “flexible translation principle” to me, but it is not my invention or property. If you care to read the endnotes of my rejoinders, you can see the source: Ingo (1990), pp. 79–81. This principle doesn’t mean irresponsibly changing the words merely for the sake of changing them, as you insist, thus misrepresenting and ridiculing the case. I do not condone relativism.

It seems to be an incontestable fact that my translation is fluent, but even this is considered a flaw. Allegedly the fluency and my “flexibility” has led to confusing conceptual nuances and distinctions, but not a single instance of such confusions is provided; you merely quote Bergman & Paavola’s opinion that Vehkavaara has done so rightly; unfortunately he hasn’t. Once again, your statement is based upon hearsay, and in my rejoinders, I severely questioned Vehkavaara’s claims and expertise. (Also Vehkavaara had a double role in the process, which I had to point out. He has no competence in linguistics, and barely can spell his own name. You really trust him?)

As for the Peirce quote on page 49 in your book, I would definitely not have translated sense and feeling interchangeably but kept them distinct. Should I translate “What Is a Sign?” into Finnish, I would probably use tuntemus or tunne for feeling and perhaps something derived from aisti for sense. Especially the following passage on page 53 grossly misrepresents and ridicules the flexible translation principle and projects on me choices that I definitely would not make and desires that I don’t feel:

“[...] that Lång embraces with his ‘flexible translation principle’ (joustokäännösperiaate). We’ve seen Peirce (EP 2: 4) using ‘sense’ and ‘feeling’ almost interchangeably, without defining or differentiating them, certainly without theorizing them; Lång would almost certainly want to translate them flexibly, using whatever term seems contextually appropriate (tunne in some places, taju in others, possibly tuntemus in yet others), possibly collapsing them into a single term in Finnish (say, tunne).” (Semibold emphasis added.)

Such description does not correspond to what flexible translation principle really means in translation studies – not irresponsible, whimsy, unnecessary & unmotivated changes, altering or collapsing words for the mere sake of it. Another such deception is to mistake a mere difference in the grammatical construction of two words for a distinction between the ideas they express. As Rune Ingo clearly states in the passage mentioned in my references (in his book Lähtökielestä kohdekieleen), changes only may be done when they are necessary, not just for the sake of altering things. Also a translation must reflect the vocabular variability of the source text. Neither do you provide examples from my translations to support such a view. You are confuting a straw man. Perhaps you should familiarize yourself with the principle in question before whacking it blindly?

I could have suggested you other passages from Johdatus which would have been interesting to analyze in terms of nearly synonymous terms as used by Peirce, namely the articles “The Fixation of Belief” and “How to Make Our Ideas Clear.” During the preparation of the anthology, we had a lively debate about the key terms like belief, opinion, notion, and idea. According to the philosophers, all these terms have a clearly distinct semantic target in Peirce, but in my view he used them loosely on a single thing; he did, nevertheless, refer to his “inordinate reluctance to repeat a word” (CP 5.402). Similarly, the German translators in the 1960s seem to have preferred the word Überzeugung ‘conviction’ in many cases (instead of, say, Glaube). Still, I retained the variability as well as it was possible.

Therefore your speculations are slanderous and untrue. You really should have consulted the person discussed before sending such an arrogant contrivance to the publisher. Minu arvates on kvaliteedi hindamine Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastuses selle käsikirja juhul väheke nurjunud. Presumably you have been misled by the one-sided and malevolent opinions of Bergman & Paavola and others. After all, you have not provided a single passage from the anthology to illustrate the allegedly constant and numerous problems caused by the flexible translation principle, or rather your distorted version of it. And from a copyediting point of view, one cannot correct “mistakes” you refuse to list.

Let’s take one easy example from Ingo’s book (p. 80). The following is clearly an idiom: It is raining cats and dogs. If I wished to make Bergman & Paavola look silly, I would make them translate the sentence thus: “Se on satamassa kissat ja koirat.” Perhaps they might actually render it so. An appropriate Finnish translation is of course Sataa kuin saavista kaataen (in other languages: Il pleut à verse, Regnet står som spön i backen).

13. Instead of my rendering, however, you chose to analyze the translation of “What Is a Sign?” by Bergman & Paavola. As you are not a native speaker of Finnish (admitted on p. 56), you cannot be expected to assess the clumsiness of their achievement. Even their heading sounds off-key: “Mikä merkki on?” In fluent Finnish, the word order is reversed in cases like this: Mikä on merkki? (Cf. titles like Kuka on kristitty, Mitä tapahtui Urho Kekkoselle, Mitä tapahtuikaan Baby Janelle?, the Finnish distribution title for What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? They do not read: “Kuka kristitty on,” “Mitä Urho Kekkoselle tapahtui,” “Mitä Baby Janelle tapahtuikaan?”)

Their translation is poor quality (similarly as Vehkavaara’s own excerpt which I discuss below); I doubt any publishing company would hire them based on that masterpiece. See how incorrectly they use participial constructions, for instance. Their rendering should be completely rewritten by a professional translator and copyedited before publication. It is not even an amateurish tinker because they violate the grammar of Finnish without realizing precisely what they are doing; there is something autistic in their approach as their translation doesn’t appear to be aimed at a reader anywise – but a foreigner cannot recognize this because they are mimicking the said foreigner’s mother tongue.

Let’s have a quick and superficial look at Tommi Vehkavaara’s book review, too. He couldn’t even get the heading right: the printed version reads, “Mielen merkillisisyydestä.” That means: ‘On the Signal Paternity of the Mind.’ Perhaps he intends to say that Peirce is the mental father of sign studies, or that all signs are of mental origin? No, in the Web version he has it corrected: “Mielen merkillisyydestä.” This makes more sense: ‘On the Peculiarity of the Mind.’ Later he translates a sample from Peirce’s article “The Ethics of Terminology,” and in his translation uses expressions like “positiivinen tarve” and “pehmeät ajattelijat.” In Finnish, these do not mean anything: they are not everyday language, they are not oxymora, they don’t even work as metaphors or spoonerisms – they are nothing but silly, moronic, confusing combinations of words, rendering literally and helplessly the English-language expressions positive need and loose thinkers. A child might produce such “translation” attempts.

It is impossible and vain to discuss the naturalness or fluidity of a translation with such bunglers – it’s like arguing about colours with a colour-blind person who refuses to admit that she cannot discern the colours similarly as a normal person does. With her own eyes, she sees some colours and cannot understand why others claim that there be separations she doesn’t discern. Unconsciously she may gather that she is in some way inferior because she notes that others can actually achieve things by utilizing separations she cannot grasp. Because of her neurological defect, she cannot move to another mode of seeing and perceive colours like others do, then return to her default state and compare the two modes of seeing and confess that there are indeed additional colours in the spectrum; no, she is a prisoner in her neurological setup and cannot ever learn to perceive colours any better. She may react with narcissistic anger if you keep maintaining that her vision is more limited than that of yours. So there is both a psychological and a neurological aspect in her attitude. Similarly a tone-deaf person cannot appreciate melodies; but probably she must confess to herself that some others seem to be making a lot of money with certain melodies. Further, the language abilities of a person can be restricted by different stages of aphasia and aphasic person cannot usually learn to overcome her disability; rather, it keeps getting worse.

It is peculiar indeed that one should come to think of conditions like autism, aphasia, colour blindness etc. when reading the translations my critics produce for themselves.

14. A major and disquieting problem in your book is that you have actually not read my translation anthology, although you frame it as a case. Your scant references point to four (4) pages of the 480-page volume, mostly to the preface; rest of your views and examples seem to be based on the criticism of Vehkavaara and Bergman & Paavola’s defense of it, that is, on mediate and partisan sources. Those of your readers who do not understand Finnish and cannot access and evaluate Vehkavaara’s review or my rejoinders have to take your word for it and that isn’t worth much, I’m sorry to say. You should have clearly stated that you only “analyze” the debate and not the actual translations presented in the 2001 anthology.

There is also a consequent problem: first you establish a distorted version of my work and opinions and then use this imaginary tool – a sword of straw – to bash the views of Dinda L. Gorlée. I find that hardly persuading.

15. When discussing the words icon and kuva (p. 57–58), you could have mentioned there that icons used in computer interfaces are sometimes called kuvake in Finnish. Perhaps Peirce’s icon could be translated using some similar derivative?

16. On pages 166–67 you dissect the German-language sentence:

“Was für Sprachspiele kann, der die Furcht nicht kennt, eo ipso, nicht spielen?”

You claim there’s a comma error, but one can also argue that the main clause is missing the subject, or alus, as we hard-boiled Fennicists would call it:

“Was für Sprachspiele kann der, der die Furcht nicht kennt, eo ipso, nicht spielen?”

“Was für Sprachspiele kann derjenige, der die Furcht nicht kennt, eo ipso, nicht spielen?”

“Was für Sprachspiele kann der, welcher die Furcht nicht kennt, eo ipso, nicht spielen?”

Here the commas are in place and the sentence can easily be perceived and understood. My personal guess is that it was a slip of the typist to exclude the repetitive pronoun der, der. Of course the sentence is grammatically correct in the shorter form as well, albeit archaic. In that case, the first comma is not obligatory, depending on how you analyze the structure of the sentence.

17. In the same passage you wail:

“Perhaps there’s an arcane Finnish comma rule that I don’t know about, governing the insertion of Latin phrases into Finnish sentences?”

Are you not a professional linguist? Don’t you know how to find out things like this? Ignorance isn’t power. There are books and articles that explain the punctuation rules of the Finnish language in great detail. I would recommend Sari Maamies’ article “Pilkku” in Kielikello issue 3/1995. To clear up your self-inflicted dubiety expeditiously, I mention that usually a comma isn’t necessary, but it is left to the discretion of the writer to decide if a Latin phrase is loose enough to be separated from the sentence with commas. In hoc casu, I find both options possible, but as the German original has commas, I would use them in a Finnish translation as well.

18. The English translations you provide for the Finnish quotes are mostly appropriate, but there are inaccuracies (incorrect word choices mostly) which I need to point out:

the resistance scholars feel → the resistance felt (41)

a scholarly vocabulary derived from Finnish roots → an indigenous scholarly vocabulary (41)

homegrown words → indigenous words (41)

a homegrown vocabulary → an indigenous vocabulary (41)

to facilitate the reader’s understanding → to facilitate the reader’s task (45)

her expertise-capital amassed from reading Peirce in English → her expertise-capital in the English language (45)

reflecting sympathetically on its potentials → deliberating sympathetically over its potentials (45)

intrude excessively → intrude excessively, violating the Finnish language (247)

for a single translator to achieve → for a single person to achieve (247)

by teams of translators representing → by teams of several persons representing (247)

we should be striving in this direction → we should be striving in this direction more arduously (247)

On page 160, your proposed translation is not grammatically correct Finnish: “Annahan luonto puhuu [...].” Did you mean “Annahan, luonto puhuu” or rather “Annahan luonnon puhua”? — Small errors: “lähtötekstiä” is spelled without a hypen (p. 47), “ad hoc -ratkaisuihin” is spelled without a dash (p. 246). In the Index, Georg Henrik von Wright should have been alphabetized under W as Wright, Georg Henrik von (on p. 279; cf. p. 235).

19. Twenty-one years have now passed since my Peirce anthology was published. The first edition sold out soon and the book has been out of print for years. In spite of this, Paavola and his posse have not been able to produce a better (superior) collection of translations, not any kind of a collection at all for that matter, only nagging. Can this be called inefficiency by now?

So I’m getting to the final point: why this letter now? — Last summer I had the opportunity to spend three months revising Johdatus tieteen logiikkaan ja muita kirjoituksia thoroughly and preparing a new edition. I reviewed the entire translation, reread all feedback from 1998–2003 and made hundreds of changes, large and small, improving the book considerably; some sections were rewritten (or rather retranslated) and two additional essays included. I restored the section numbers to two articles and the big table to “Reply to the Necessitarians,” and expanded some footnotes with material from Karl-Otto Apel’s German edition.

Also, I amended several long and complex sentences that I had perceived and analyzed incorrectly, and in a few other ones restored short clauses that were missing from such sentences because of my inadvertence. For some odd reason these mistakes were never pointed out by my critics – perhaps because they cannot grasp such sentences any better.

On the continuum presented earlier, I backed a little and moved from the Finnlandisierung end slightly closer to the middle. For instance, the translation no longer uses such words as tuonpuoleinen, alus, and maine.

I corrected all the faults I noticed (including those collected into the errata list) and I’m much happier with the revised version, published this week. If the first edition was a train wreck, I hope the second one is merely a singelolycka på cykelleden. I won’t exclude a third, still improved edition in some distant future, God willing, this time prepared in collaboration with a new generation of friendly-minded and non-busy experts, but even that is not going to be a walk in the park.

The second edition also has a short new preface. In it, I discuss the reception of the book and mention Dr. Ritva Hartama-Heinonen’s contribution. Your book is not mentioned, however, because I don’t consider it useful. Still, some of your allegations and misrepresentations are so inappropriate that I cannot just let them be; that’s why I’m writing this open letter: to right certain details and to put things in perspective. There is also another viewpoint to the quarrel, that of the accused one, neglected so far.

You are not the only one who can make others appear ridiculous, and in careless hands such modus operandi may backfire.

I will not remain your humble servant.

Yours sincerely, [signature]

Markus Lång, Ph.D.

info copy Minervan Pöllö, Helsinki