© Markus Lång 2002

This review was first published in Lewis

Carroll

Review, issue 23 (July 2002), pp. 9–13.

Quotations

to be made according to the Web version.

A Finnish-language version was published

in Kulttuurivihkot,

issue 2–3/2003 (vol. 31), p. 8–9,

and reprinted in Valitetut teokset, pp. 261–264.

Alice Performing

|

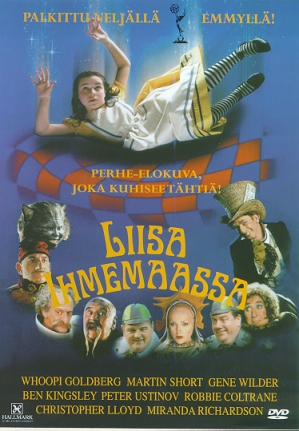

Liisa ihmemaassa · Alice in

Wonderland Directed by Nick Willing Based on the book by Lewis Carroll Written for television by Peter Barnes Music by Richard Hartley © Hallmark Entertainment & Babelsberg Film GmbH & NBC Entertainment 1999 Runtime: 128′05″ (main feature), 1′07″ (TV spot) Audio: English, Dolby Digital 2.0 (surround) Subtitles: Swedish, Finnish, Danish, Norwegian Aspect ratio: 4 : 3 (full frame) Format: PAL Regional code: 2 Future Film DVD Video 51031, Finland 2002, € 13.30 |

In spite of the obvious problems with visual realization, the Alice books seem to be quite popular subjects for films and TV shows. According to the sleeve-note of this particular DVD release, there are thirty feature films based upon Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland alone. According to the Internet Movie Database and other sources, the real count may be slightly smaller.

The Alice stories pose a great challenge for filmmakers because of the dream-like incidents: changes of size and place, metamorphoses, and peculiar characters and animals. Actually the subject suits better for film animation as many visual tricks can be achieved very naturally in that medium. Walt Disney’s version (Alice in Wonderland, 1951) is excellent in this respect, and actually quite faithful to the original story, compared with the version reviewed here.

One of the first things one looks at in a film version of Alice is the special effects: how do they function, do they seem natural and plausible, do they back up the story or distract from it? (The history of the cinema could be written through the illusions and tricks, from Georges Méliès to George Lucas.) This latest production of Alice in Wonderland (1999) promises to provide the audience with a visually enjoyable story, thanks to the advanced technology & millions of U.S. dollars spent. As it is a video production and not shot on film, the special effects can be accomplished with less effort, because of the limited resolution of the TV screen.

When viewing the final product — and this adaptation tastes more of laborious product than spontaneous art-work — one is presented with some surprises and several quite conventional tricks which still feel and look like manufactured effects, not actual states-of-things. Some visual gags seem surplus, like the stretching arm of the Mad Hatter (is it supposed to be funny?).

To put it bluntly: the quality of the visual effects is often mediocre, and the sets seem studio-like — Alice does not, for instance, meet the Gryphon and Mock Turtle out-doors, or by the sea, as John Tenniel’s drawings would suggest. The effects are often vivid but not fully seamless nor photographically realistic, unlike those by Industrial Light & Magic. The video image on this DVD seems to be an NTSC → PAL transfer, so it is not very sharp in spite of the digital medium.

Very detailed effects create the problem that they do not leave room for the imagination but give the viewer one ready-made interpretation instead, unlike adaptations, like Jonathan Miller’s (Alice in Wonderland, 1966), that use minimal effects. Overwhelming special effects distract attention from the acting and from the inner meanings of the story to the surface level. (The new Star Wars films suffer from this problem, too.)

The animal characters were created by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop. They look very lively, often they have an actor inside, and you can believe in them: they are not mechanical puppets but living creatures. The White Rabbit, however, made me wonder why he must behave like a nervous Duracell bunny (this is done with video editing). The flamingoes and hedgehogs are very lively but the humour with them is too pointed as well.

This TV version has an impressive cast of actors, raising expectations about the show. Just think of a feature with Whoopi Goldberg, Gene Wilder, Ben Kingsley, Peter Ustinov, Joanna Lumley, Robbie Coltrane, Christopher Lloyd and more! How are their personalities and charisma utilized? Rather poorly, one must admit. There are only few memorable moments: Whoopi Goldberg’s grinning Cheshire cat and Robbie Coltrane’s Tweedledum. Some actors have been thrown into almost embarrassing role-performances, like Gene Wilder’s Mock Turtle and Christopher Lloyd’s White Knight. And why must Miranda Richardson’s Queen of Hearts shriek all her lines so shrilly? Martin Short’s Mad Hatter is rather manic, anxiously acting out.

I had my reservations concerning the alterations made to the story line, too. Basically the plot follows Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and takes a few scenes from Through the Looking-Glass — the garden of live flowers, the Tweedles, and the White Knight — but there are some essential alterations in the basic story that affect the whole atmosphere of the adventures.

In the beginning of this dramatization, we meet a little girl Alice (Tina Majorino) who is afraid of giving a musical performance: she is supposed to sing “Cherry Ripe” (a song by Robert Herrick and Charles Edward Horn) to an audience of elderly Victorians, friends of her mother and father. She is suffering from stage-fright and is under a stress. Consequently, she escapes to the garden and hides there. Then we must assume that she falls asleep.

If you think of the setting of the original story, the change is notable. In the book, Alice has nothing to do and her dreams arise spontaneously from her imagination; they serve no utilitarian purpose like this dream in Peter Barnes’ and Nick Willing’s adaptation. The original story told about a little girl who is growing up and isn’t quite sure about her identity; the world of adults seems bizarre enough. Many philosohical problems can be found hidden between the lines.

In the new version, Alice’s dream is just some kind of a stress-related syndrome, which eventually helps her overcome the fright. Even the Wonderland characters tell her that they are there to help her because she needs them. Eventually, Alice feels “confident” and the dream may come to an end. She now finds herself able to perform but the song she chooses comes from her dream: “The Lobster Quadrille”.

That overall modification has taken the plot quite far from the original ideas of the author. Lewis Carroll was critical of utilitarian poetry and wrote some unrivalled parodies of it, like “How doth the little crocodile” and “Father William”. Now his whole dream fantasy is actually transformed into a stress-related syndrome, making the atmosphere of the story feel strained. The humour, for instance, becomes desperate and the relief achieved seemingly only, because anxiety is lurking behind the scenes all the time.

Because the filmmakers wanted to include all the Wonderland scenes plus a few from the Looking-Glass, they had to cut everything short. In this Wonderland, it would be nonsensical to write: “So they sat down, and nobody spoke for some minutes.” (It is always pleasing to see our Finnish customs obeyed elsewhere!) The dialogue and poems are shortened and occasions simplified everywhere but this is done somewhat clumsily so that many situations are no longer funny or spontaneous, rather they feel dutiful and hurried. On the other hand, some dialogue and numbers like “Auntie’s Wooden Leg” have been added. They are limp indeed. The only pun I actually could laugh at came from the March Hare: “Waiter, waiter, there’s a hare in my soup!”

It would be pointless to list all the alterations made to the original plot, characters, dialogue and locations. Of course a book cannot be filmed literally, one is expected to adapt for the new medium, but many of the changes felt as if they were made just for the sake of change, and, in my opinion, they are not for the better. The whole story has been transformed into conventional problem-solving.

Most Alice adaptations rely very much on music and in this respect Willing’s version makes no exception. Richard Hartley has written a pretty, harmless score in 19th-century style, which is easy to listen to; I thought the “Turtle Soup” quite agreeable. (I don’t know if this setting is related to James M. Sayle’s song. A tune can be parodied as well as the words.)

As this DVD release of Alice in Wonderland is a Scandinavian pressing, it has no subtitles in English but in Finnish (by Timo Kivistö), Swedish (Barbara Westin), Danish (Henrik Holden Jensen), and Norwegian (Stephan Lange Sandemose). Competent only in the first two languages, I shall limit my brief comments to those. — The Finnish and Swedish subtitles seem accurate, although the Finnish ones have some lapses. The Mad Hatter’s song is most probably “Auntie’s Wooden Leg”, but according to the subtitles, “Artie’s Wooden Leg”. The three other translations seem all to refer to an “auntie”. Another is found in the court-room scene: the Queen orders the trumpeters to try the fanfare again “on soprano sax”, but according to the Finnish translation, “Try again one octave lower!”

In transmitting the Carrollian puns and poems the Finnish subtitles rely on the translations of Kirsi Kunnas & Eeva-Liisa Manner (1972/74) — stating a debt to a translation “by Juva and Manner”. (This probably refers mistakenly to Kersti Juva, another renowned translator, resident in Oxford, with authors like J. R. R. Tolkien and Laurence Sterne in her résumé.) This solution is fully acceptable, although there are more up-to-date translations. The new puns, however, posed problems to the Finnish translator: e.g., the “Great Cat Massacre of ’28” (?) was a cat-as-trophy (in Swedish it’s almost possible: “katta-strof”), as well as the “hare in my soup”. If the translation is made directly from the audio track, puns like these may go unnoticed.

I wasn’t very happy with this new adaptation of Alice in Wonderland. The story has been reshaped but not for better; the acting is exaggerated, the humour strained; the whole thing arises from stress and the moral is utilitarian: you have to perform, you can’t query the demands made on you, but the show must go on. I cannot rank this version among my personal favourites. Of course, this is better than the version directed by Harry Harris (Alice in Wonderland, 1985) of which one cannot watch more than the opening credits, but it falls well short of the Disney and Miller versions, for instance.

The future seems forcefully exciting. Rumour has it that Wes Craven is directing an Alice film, based upon the computer game by American McGee. “Off with their heads!” will be executed then by might and main, I guess.