© Markus Lång 2009

A shorter version of this review

was first published

in Lewis Carroll Review, issue 40 (April, 2009), pp. 5–6.

A Finnish-language version was published in

Kritiikki:

Nuoren Voiman kirjakatsaus, issue I (2009), pp. 50–52,

and reprinted in Valitetut teokset (2014), pp. 275–279.

Tongue’s Labour’s Lost

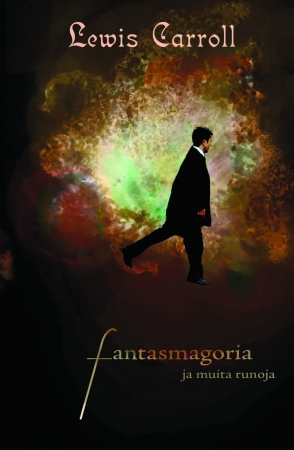

| Lewis Carroll Fantasmagoria ja muita runoja [Phantasmagoria and Other Poems] Translated into Finnish by Ville-Juhani Sutinen Savukeidas Kustannus, Turku (Finland), 2008. € 18.90 162 mm × 98 mm, 138 pp., p/b ISBN 978-952-5500-34-9 |

There is no doubt that Lewis Carroll was a master of rhyme and metre. Therefore those who seek poetic pleasure from this new Finnish translation will be sadly disappointed. Ville-Juhani Sutinen has translated Phantasmagoria and Other Poems (1869) into Finnish, but he has chosen not to observe the rules of metrical poetry. So he has taken a route very different from that of other Finnish translators of Carroll, like Kirsi Kunnas and Alice Martin, who have used rhyme and metre as flawlessly as the author did.

There is no doubt that Lewis Carroll was a master of rhyme and metre. Therefore those who seek poetic pleasure from this new Finnish translation will be sadly disappointed. Ville-Juhani Sutinen has translated Phantasmagoria and Other Poems (1869) into Finnish, but he has chosen not to observe the rules of metrical poetry. So he has taken a route very different from that of other Finnish translators of Carroll, like Kirsi Kunnas and Alice Martin, who have used rhyme and metre as flawlessly as the author did.

The translator’s preface alone should alarm a critical reader from proceeding further. Mr. Sutinen ponders half-seriously that Carroll molested sexually the Liddell girls, abused narcotics, and that he was actually Jack the Ripper. (He spells the name as “Liddle” and obviously thinks that Carroll photographed the Liddell girls in the nude.) After such insinuations, a long, pedantic, ostensible self-criticism follows which shows that the translator is more interested in his own tinkering than in Carroll’s poetry.

In his translation, the translator has tried to imitate the verse structure of the original poems to a certain extent but he fails so utterly that one has to wonder how a book like this could be printed in the first place. It is mostly embarrassing to notice rhythmic failures and faulty rhymes in almost every line of poems which represent such a perfection in the original language. It may be difficult to translate poetry and maintain the formal excellence, but the translator needs to work up his or her ideas until they attain perfection. The problem with this translation effort is that the translator has accepted his first rough whim and then stopped. It is unclear to me whether this is based on choice or on indifference.

In my opinion the worst failure in this collection is the translation of “Hiawatha’s Photographing”. The translator has not realized that he should have used here a poetic device which has a Finnish background: the Kalevala metre (trochaic tetrametre). As we know, Carroll parodied here Henry W. Longfellow’s epic The Song of Hiawatha (1855) which was inspired by a German translation of the Finnish national epic, Kalevala. (In his preface, the translator writes nonchalantly about “a chanson by Henry Wadsworth.”) The Song of Hiawatha has been translated into Finnish by A. E. Ollilainen using Kalevala metre, and a proper translation of “Hiawatha’s Photographing” should have been — at least to a certain amount — a parody of it.

The Kalevala metre is based upon alliteration, but in his preface the busy translator explains how he has “applied into use a perpetual, almost unnaturally flowing rhyme formula in order to be able to manifest in it the corresponding factors that have been created mostly by the rhythm in the original version” (p. 11–12). The end product is quite unnatural indeed, and the attempted rhymes are incorrect because the translator does not even discern stressed syllables from unstressed ones. Also, the translator has not comprehended that the quasi-prose introduction to “Hiawatha’s Photographing” is in Kalevala metre, too.

This little book cannot be recommended to anyone. The preface is full of misconceptions, typographical errors and off-grade Finnish. The poems limp. The translator simply is not up to this kind of poetry. The translations are joyless and uninteresting, and we have to manage without the illustrations. The art of poetry has been exorcized from this book altogether.